Mystery Writer and former skip tracer Terry Ambrose interviewed me about Bum Luck for his blog,, which I’m reprinting here. The subject of former NFL players dying of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) has been in the news since publication of the novel in which linebacker-turned-lawyer Jake Lassiter suffers symptoms of brain damage.

By Terry Ambrose

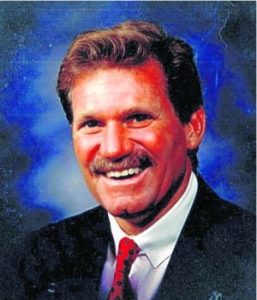

The author of twenty novels, Paul Levine won the John D. MacDonald fiction award and has been nominated for the Edgar, Macavity, International Thriller, Shamus, and James Thurber prizes. A former trial lawyer, he also wrote twenty-one episodes of the CBS military drama JAG and co-created the Supreme Court drama First Monday starring James Garner and Joe Mantegna. Levine has just released the twelfth installment of the Jake Lassiter series, Bum Luck.

From Small Screen to Page

“Both writing for television and writing novels are rewarding and challenging in their own ways,” Levine said. “On television, it’s a shared responsibility. Director-showrunner-actors-network executives. The vision doesn’t belong to one person but is diffused. With novels, the writer is a one-person band.”

While Levine prefers the independence of writing novels, he enjoys the pace of TV writing. “There’s something about the immediacy of television—script to air in six weeks—that is appealing. Also, I believe television scribbling helped my book dialogue.”

Levine said, “Justice as an ideal is an underlying theme for me. The difficulty of achieving justice is the heart and soul of Bum Luck and the entire Jake Lassiter series. That’s reflected in Jake’s inner voice with lines like, ‘Justice is the North Star, the burning bush, the holy virgin. When you fail to attain it, fight for the next best thing. Rough justice is better than none at all.’”

CTE: The Burning Issue Behind Bum Luck

Attorneys defend guilty clients all the time—and that knowledge is also behind the Lassiter series. “The dilemma of a lawyer defending a guilty client has always fascinated me,” Levine said. “In Bum Luck, Jake Lassiter seeks vengeance, or vigilante justice, against his own client.”

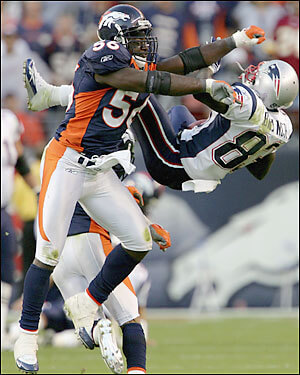

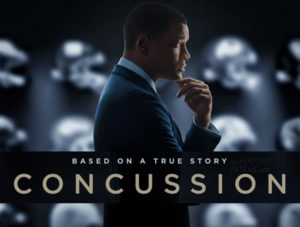

That’s right, Jake Lassiter, in the opening lines, announces his intention to kill his client. “Why would Lassiter, after all these years representing guilty clients, feel this way?” Levine said. “He might be very ill. Remember that he’s a former second-string Miami Dolphins linebacker who went to night law school and became a trial lawyer. In Bum Luck, Lassiter suffers symptoms indicating he may be in the early stages of always fatal Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

Levine said his primary goal is to entertain. “That starts with character. I aim for rich, complex, layered and often humorous characters who tell me the plot.”

Note: Just this week, The Journal of the American Medical Association reported on a harrowing study: 110 of 111 former NFL players who had shown symptoms prior to death were found after autopsies to be suffering from CTE. Recently, Sports Illustrated wrote about legendary linebacker Nick Buoniconti who, among others from the Miami Dolphins’ Super Bowl teams, is suffering from CTE. I previously blogged about the link between repeated blows to the head and CTE in a blog entitled: “Are Concussions Killing Jake Lassiter?”