By Paul Levine

Anthony Doerr ruined my vacation. He also destroyed the confidence of blossoming writers and set an impossibly high standard for other novelists.

What’s the matter, Tony? Winning the Pulitzer wasn’t enough?

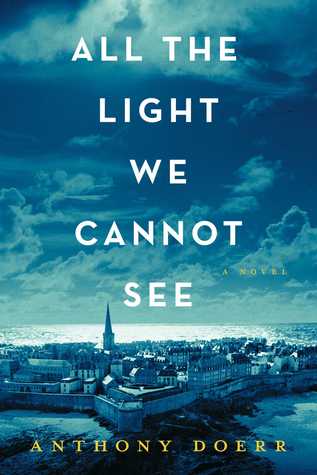

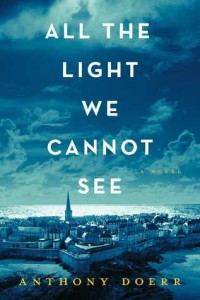

Doerr is the author of All the Light We Cannot See, the lyrical, compassionate, hauntingly gorgeous novel that won this year’s Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

And it’s kept me indoors on vacation. Fleeing the Miami heat and humidity, my wife Marcia and I escaped to Boulder, CO. My intentions were sincere. I’d hike, bike, sample the local brews. But instead of enjoying the glorious Colorado outdoors, I’ve been hunkered down on the porch, immersed in All the Light We Cannot See, reading and re-reading many of its elegant passages.

“All the Light We Cannot See” an Epic Tale

The novel is an epic masterpiece of fate and love, myth and imagination, humanity and inhumanity, tenderness and cruelty, and what happens to dreamers during the utter insanity of war. It’s the story of a blind French girl and an orphaned German boy and how they’re destined to come together during the darkest of times. Indeed, it’s a novel of light and darkness.

The portrait of 1940 Paris, on the eve of war, rings true. SPOILER ALERT: Germany invades France. SECOND SPOILER: The French put up as much resistance as an éclair to a butcher’s knife.

All the Light We Cannot See overflows with melodic phrases, magical imagery and dazzling wordplay. Of the blind girl who learns to navigate the streets from scale models lovingly built by her father: “She walks like a ballerina in dance slippers, her feet as articulate as hands, a little vessel of grace moving out into the fog.”

Most writers struggle to describe characters’ voices in original ways. Not Doerr, who floored me with this: “His voice is low and soft, a piece of silk you might keep in a drawer and pull out only on rare occasions, just to feel it between your fingers.”

There is even a rumination on the possibility of life after death. In less than a page, the author posits a theory more persuasive than a thousand Sunday sermons. HINT: Souls travel on electromagnetic waves.

Oh, the Damage to Writers’ Fragile Egos!

So here I sit – on the front porch – entranced as I finish this unforgettable novel. But I complain not just on my behalf. Consider the young writers studying their craft at Stanford, Iowa, and the back booths of countless Starbucks. Does Doerr comprehend the fragility of their egos? The plenitude of their neuroses? Even without this daunting book, they fear their work will just add to the tsunami of swill, the endless tide of mediocrity pouring from laser printers and overflowing publishing platforms.

So, yes, I blame Doerr for nipping the buds of blossoming writers. And what about the environmental damage? The hardcover I purchased is from the book’s 37th printing. That’s a lot of felled trees, Mr. Doerr. Consider that, too, the next time you sit down to work your literary magic.

Paul Levine’s “Bum Rap” is available in trade paperback, ebook and audio.