I came to Hollywood for the health insurance.

That’s right. I lusted after cheap meds, not fame and fortune, when I migrated from Miami to Hollywood 17 years ago. And why not? A doctor’s visit costs ten bucks at the industry-subsidized Bob Hope Health Center. I quickly learned, however, that writers pay their dues in many other ways. Even mystery writers.

Before I traveled west, I thought Hollywood writers rolled into work around 11 a.m., scribbled for a couple hours, drank their lunch at Musso and Frank’s, then cracked wise with starlets the rest of the day. Like Bogart, who came to Casablanca for the waters, I was misinformed.

I quickly learned that television scribes are skilled craftsmen who work damn hard, sometimes all night while cameras roll. The writing itself is tougher than it looks. One-hour dramas employ the same three-act structure as plays and novels. Yes, it’s still the dramatic form advocated by Aristotle. Act one is exposition; act two is complication; and act three is resolution.

HOLLYWOOD PRODUCER: “Aristotle said that? Get me his agent.”

An overriding factor in television writing is the restraint of time. Want to craft a one-hour drama? After commercials, you’ve got 43 minutes to tell your tale. Stream-of-consciousness writers need not apply. Mystery writers who are strong on structure fare better.

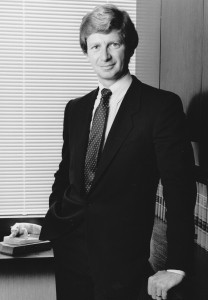

I came west in 1999, sneaking into TV at such an advanced age that the Christian Science Monitor dubbed me the “oldest rookie writer in Hollywood.” I had already been a newspaper reporter, a trial lawyer, and a novelist, so I have a track record of either taking on new challenges or being unable to hold a job, depending on your point of view.

I began doubting the sanity of this latest move my first day on the Paramount Pictures lot. My dungeon of an office in the Clara Bow Building overlooked a dumpster behind the commissary, and my window air conditioner whined like an F-14 taking off from an aircraft carrier.

Mystery Writers Are Their Own Bosses. TV Writers Not So Much.

Years earlier, as a lawyer, I enjoyed a view of Bimini from the penthouse of a high rise on Miami’s Biscayne Bay and lunched on stone crabs and passion fruit iced tea at the Bankers’ Club. Later, as my own boss, I wrote eight novels at home in Coconut Grove, parrots squawking in a bottlebrush tree outside. Now, with kamikaze horseflies from the dumpster smashing into my window, I was low man on a staff of six writers. As well I should have been. When I got to Hollywood, I didn’t know a smash cut from a cold cut. How did I get here, anyway?

I’d been bitten by the Hollywood bug in 1995 when the late Stephen J. Cannell produced an NBC movie-of-the-week that was adapted from my first novel. I began dabbling in Hollywood long-distance. I wrote an action-adventure feature for Cannell’s company. Think Die Hard in a missile silo. I wrote the first draft of The A-Team feature screenplay that likewise went nowhere. I penned a computer hacker pilot for ABC. Five similar pilots were commissioned by the networks that season; none got on the air. I wrote a miniseries for CBS, which also was never produced. I was beginning to learn of a world where writers were unionized and got paid even though their work was shelved — literally — stacked on shelves with hundreds of other dusty scripts.

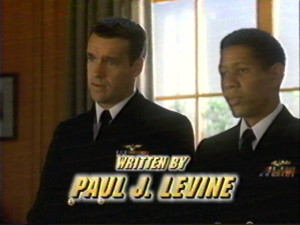

I also free-lanced two episodes of JAG, the CBS military drama. When they aired, I had the novel sensation of listening to actors read my words aloud.

Mystery Writers Wondered if I’d Sold Out.

Then Don Bellisario, the creator of JAG, offered me a staff position. I considered the alternatives. Stay in Miami with the mosquitoes and no book deal. Or go to L.A. and get a paycheck plus that free health insurance. Goodbye mosquitoes. Hello coyotes. (The four-legged scavengers, not Hollywood agents.) My friends among the mystery writers watched from afar with alarm. Had I sold out? Would I be eaten alive?

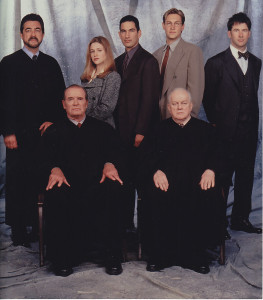

I ended up writing 20 episodes of JAG and also co-created with Bellisario First Monday, a drama set at the Supreme Court. The show, which was based loosely on my novel 9 Scorpions , this year was named one of the “ten great Supreme Court novels” by the American Bar Association Journal. It is now available as an ebook, retitled Impact. First Monday gave me the opportunity to work with James Garner, Joe Mantegna, and Charles Durning, three terrific actors. In fact, the entire cast was fine. But we, the producers and writers, failed when we tried to jazz up the stories.

In reality, most of the drama at the Supreme Court takes place in the Justices’ minds and is difficult to dramatize. Still, we might have been a hit, if not for our dead-on-arrival demographics: most of our viewers were between Medicare and the mortuary. After 13 episodes, we were buried in the slag heap of cancelled shows.

So was the Hollywood experience all bad? As the junior officers frequently said to the admiral on JAG: “Permission to speak freely, Sir?”

Actually, there were many satisfying moments. While TV writers remain anonymous outside the industry, an actor’s compliment on a script or several warm and fuzzy e-mails from viewers mean that someone has noticed your work. The very speed of the process — weeks, not years — from page to screen, makes the medium more intense and immediate than publishing. Then there’s the knowledge that 15 to 20 million people are paying various degrees of attention to a story you created out of a thin air. (Moments later, of course, your story vanishes into thin air).

Something else, too, something I never anticipated. Writing for TV sharpened my prose skills. I believe my writing is leaner, my plotting tighter, my dialogue zippier. And let’s not forget those regular paychecks plus pension and health benefits.

I have returned to the excruciating yet exhilarating task of storytelling with only the written word. Since Hollywood learned it could exist without my services, I’ve published four courtroom capers in the Solomon vs. Lord series. One of the books, The Deep Blue Alibi, was nominated for an Edgar Allan Poe award. More recently I’ve written four novels that bring together squabbling law partners Steve Solomon and Victoria Lord with Jake Lassiter. First came Bum Rap, in which Lassiter defends Solomon in a murder trial. The courtroom novel was the number one overall bestseller out of nearly six million books in the Amazon Kindle store in July 2015. Bum Luck, the second in that combined series, was published in 2017 followed by Bum Deal in 2019 and Cheater’s Game in 2020. In Cheater’s Game, named one of the best legal thrillers of the year by Best-Thrillers.com, Lassiter tackles the true-to-life college admissions scandal.

Solomon vs. Lord has recently been optioned (once again) as a television series. No, I’m not interested in writing the show. I’ve got my health insurance — and my sanity — and intend to keep both.